Mardi Gras: Made in China: "

During Mardi Gras in 2007, I was standing on a balcony with Shelly, a fifty-year-old woman from Oklahoma City who described herself as a housewife and a grandmother. About every three minutes Shelly performed a typical routine that many women perform during Mardi Gras on Bourbon Street. “Hey you, up there! Show your tits!” one man yelled to Shelly. “Give me some beads! Big beads!” Shelly responded, emphasizing the word "big" and "beads" as she negotiated with anonymous members of the crowd, while they bargained with Shelly on which part of her body they wanted to see. “I want those beads,” Shelly declared, while pointing to a man wearing heart-shaped beads around his neck. “You want these? Then you gotta show me those,” the anonymous man playfully yelled, pointing to her breasts. “You like these?” Shelly exclaimed, pointing to her breasts as she slowly and playfully raised her shirt and then lifted her skirt for the crowd to see. Immediately hundreds of male revelers below let out a thunderous roar as they showered Shelly with Mardi Gras beads.

Every year revelers exchange millions of plastic beads for sex and nudity on Bourbon Street, but what happens when we follow those beads from the hands that exchange them to the hands that make them? Where does the actual manufacturing of these beads that provide so much pleasure to celebrants come from? While participants are using beads to get down and dirty for transgressive thrills, the majority of the world’s plastic bead production occurs in Chinese free-trade zones that were established in the late 1970s. I had an opportunity to stay for two months inside the largest bead factory in the world: The Tai Kuen Bead Factory in Fuzhou, China, owned by Roger Wong. Those two months form the basis for my film titled MARDI GRAS: MADE IN CHINA — an exploration in a commodity chain.

MARDI GRAS: MADE IN CHINA follows the story of four teenage workers who sew plastic beads together with needles and thread and also pull them from a machine. Each story provides insight into their economic realities, self-sacrifice, dreams of a better life, and the severe discipline imposed by living and working in a factory compound. I was eventually kicked out of China under the premise of not having a journalist visa, so I continued following the bead trail to New Orleans in an effort to visually personalize globalization. What I found, and presented in the documentary, is that Mardi Gras beads were hand-crafted and made from cut glass in Czechoslovakia up until the late 1960s. Glass beads were the most popular throws at that time, but a rise in costs, political conditions overseas, and a safety ordinance that cautioned against items that might cause eye injuries all contributed to the decline and ultimate elimination of glass beads and the rise in popularity of plastic ones.

The proliferation of plastic marks the emergence of a disposable culture. Following the plastic bead from China to the U.S. illustrates how the commodity chain is connected to different people along the alienated and seemingly disconnected route.

The raw material for the beads comes from polyethylene and polystyrene — oil based liquids supplied by Chevron (and coming out of Iraq). Here, the film comes full circle. After Mardi Gras ends in New Orleans, the beads are left on the ground where some people collect them and send them as care packages to U.S. soldiers in Iraq where they celebrate Mardi Gras by tossing beads into the streets! Hence, disposable culture is exported overseas as a cultural ritual. In other words, the beads go full circle from a liquid material in Iraq, to China, to New Orleans, and back to the streets of Baghdad where soldiers exchange them in a material form.

The DIY spirit of asking questions, making art, distributing the art, and then making a new film is, for me, exactly why Etsy exists. When I look through the growing membership of Etsy, it inspires me to keep producing socially and environmentally conscious work while listening to the community members who make this possible because of their love for handmade items. Etsy connects the producer and consumer — as people — directly in a very personal way. And that is the intent of MARDI GRAS: MADE IN CHINA. If we connect the makers and buyers maybe a new economy based on fair wages and accountability is possible.

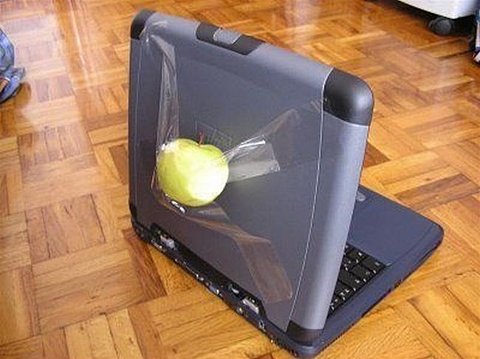

Last week, the world saw Apple’s long anticipated tablet device, the

Last week, the world saw Apple’s long anticipated tablet device, the